One pond, four species! Observing all newt species of NL at once

(Blog alleen in het Engels)

8 may, 2022

Spring has started. The flowers are blossoming, the sky is blue and

the bees are buzzing the salamanders are laying eggs! For amphibian researchers like myself the spring and the summer are great periods to conduct fieldwork. As a volunteer I monitor wild amphibians in a forest nearby my home and the 2022 season has just started. Recently I discovered all four native newt species in this forest together with some of my colleagues. The extra noteworthy thing? We found them not only within the same

forest, but within one and the same

pond, even!

Photo: Nienke Prins

As I focus on

Triturus

salamanders for

my PhD research, I became naturally interested in these, and other, amphibians. This is why I started working as a volunteer for

RAVON (Reptile, Amphibian, Fish Research/Onderzoek NL) one year ago. A forest nearby my home was appointed to me for monitoring purposes and this forest supposedly housed all four native newt species of the Netherlands. However, it had not been investigated for quite a while. I have been monitoring the forest in question for over a year now, but the last time someone monitored the waterbodies in this area before me was - I believe - around ten years earlier. Thus, I am honored that I can help out an organization like RAVON by picking up where the previous monitoring volunteer left off, so that the local database can be updated on a yearly basis again!

The forest lies somewhere in the province of

North Brabant. I like to believe that what we achieved is not something that many amphibian enthusiasts are able to do on a daily basis in the Netherlands (please, if otherwise, do not tell me; it would make me feel foolish for nerding out). I will not enclose the exact location of the pond in order to avoid a not-very-likely, but possible stampede of interested nerds who are much like myself, but who may lack the right paperwork and experience. What I can do, though, is tell you a bit about the animals that we found and what the monitoring fieldwork entails!

“Not every salamander is a newt, but every newt is a salamander.”

As you may have noticed I have used both the terms 'newt' and 'salamander' to describe the little

amphibs. Note that not every salamander is a newt, but every newt is a salamander! Salamanders are a separate group of amphibians, as are frogs and toads, which together make up the second group. People often mistake salamanders for lizards, which are not amphibians, but reptiles. I wrote an article about how you can best distinguish between salamanders and lizards (here you go). A third group of amphibians consists of caecilians, by the way. These are mysterious, relatively unknown, limbless amphibians. Interesting, but perhaps I will leave more on that for another blog post!

The newts are semi-aquatic salamanders, which means they mostly spend a part of the year living on land (through hibernation) and a part of the year living in the water (reproducing). When they are in the water, during spring and summer, they are not too hard to find. It is important that nature-lovers and biologists such as myself go out to actually search for them every now and then

- of course according to best practice guidelines and with the right permits by hand.

Why is this important? Because by doing so we can collectively build and keep a record of information on where these beautiful, cold-blooded animals occur and how their populations are doing over time. This is vital in the midst of todays'

nature,

biodiversity and

climate crises.

Photo: Nienke Prins

There are several ways to monitor amphibians; you can listen for frog calls in the evening, for instance; you can enter the ponds in a wading suit during the day while using a dip-net to catch salamanders, larvae and tadpoles; you can observe freshly-laid eggs from offshore; and you can go visit the forest by night with a flashlight to observe the animals, which are mostly nocturnal.

Before I started I was told all four native newt species lived in this area: the more

common smooth newt (Lissotriton vulgaris) and the

Alpine newt (Ichthyosaura alpestris), but also the

great crested newt (Triturus cristatus) and the

Palmate newt (L. helveticus). Some of these species are easier to find than others in the Netherlands and it really depends on the region where you search for them whether you will have any luck. The species can be distinguished by morphological characters like body size, color, patterning of the spots, and the way their belly looks. During the breeding season in spring/summer, it is also possible to distinguish the males from the females by the crests along their backs, which are most obvious/spectacular in crested newts!

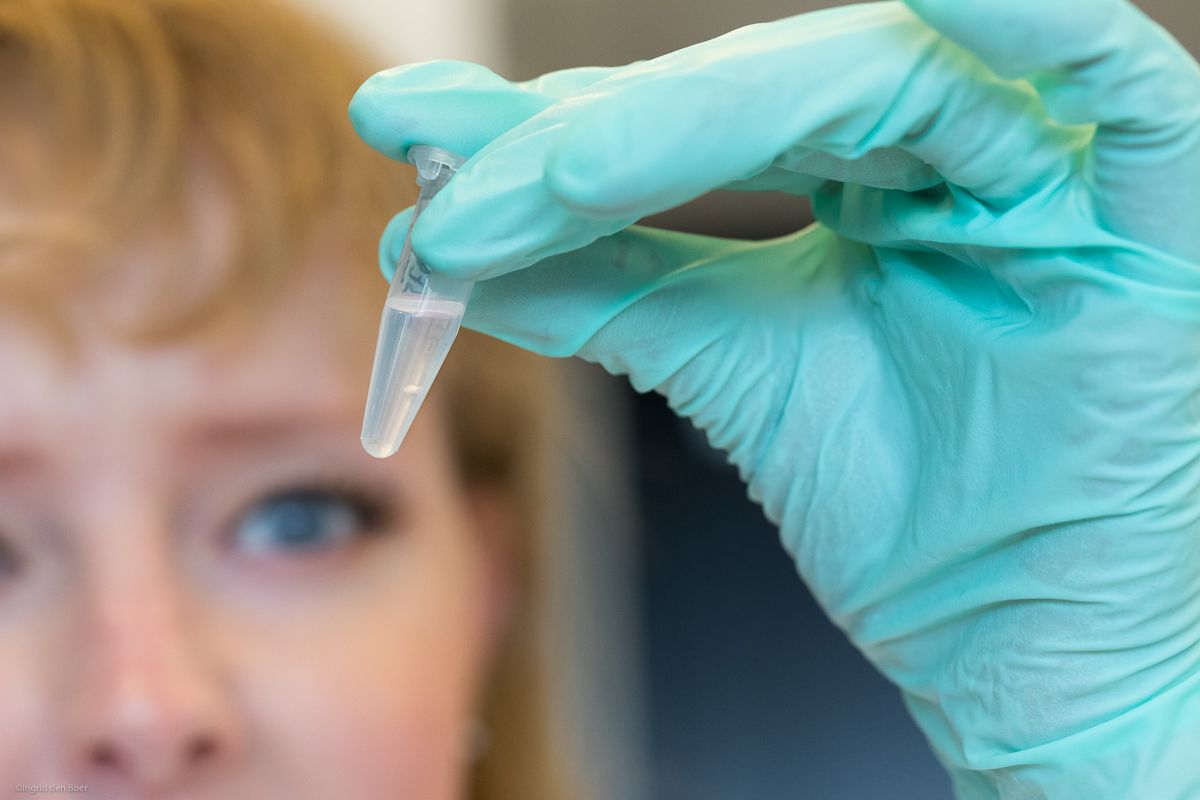

"A count, sample collection and quick photoshoot; and then they're free to go again!"

I was particularly interested in finding the locations where the crested newt might occur. I like this species the most, not only because of my research that focuses on

the DNA of

Triturus, but also because they are just so incredibly large compared to the other species and their belly pattern is amazing! I knew this species was hanging around, as I had encountered the eggs in some places... But finding the adult individuals themselves appeared to be tricky, as the crested newts hide in the deepest parts of the ponds they inhabit during the day. It was much easier for me to find the smooth newts, Palmate newts, and Alpine newts in this region.

When we find adult individuals, we count them and in a few occasions we collect some of the DNA for

scientific purposes. The animals are not harmed, by the way: they obviously may not like the quick count, the DNA sample collection (of their saliva, or of their outer body 'slime'), and the quick photoshoot as much as we do. But after this streamlined

catch-and-study

process they are immediately free to go, back to where they came from!

Over the last weeks I showed around co-workers from RAVON and from

Staatsbosbeheer and I also guided students from the

Wielstra lab at the Institute of Biology Leiden and Naturalis Biodiversity Center. I positioned some funnels the nights before any visitors came by to increase the chance of seeing/monitoring

Triturus. When one of the groups of students came by to learn about the animals, we were indeed finally able to find an adult crested newt, alongside the other three species.

Quite the quartet!

I had not observed this before. It is clear that all four of them can share ponds in regions where their habitats overlap.

That must be one cozy pool of good quality water!

Thanks for being there that day: fellow PhD candidate Willem Meilink, MSc student Nienke Prins and BSc student Jody Robbemont!

Photo: Nienke Prins

Photos & videos: a mix of several photo's from Pixabay, Pexels, and my own material. Please check with me before re-using.